The fourth volume of Proust’s Search opens on an act of surveillance: Marcel1 spies a tryst between the Baron de Charlus and Jupien the tailor2, a direct enough account—including an aside concerning the “cleanliness” of anal sex—which inspires, in turn, a long and rambling meditation on erotic complementarity and gender inversion.3 The evidence of their identities had been available for interpretation all along, Marcel insists—the trouble is, our ways of seeing are so powerfully abridged by what we expect to enter a given field of vision. “Ulysses himself did not recognise Athena at first,” he says, “It is the explanation that opens our eyes; the dispelling of an error gives us an additional sense.” You might wonder whether this is a matter of witnessing only what we wish to, but I think Proust is getting at something odder, something about the political limits of intelligibility, in other words, how the people as a body agree on what might be rendered recognizable, and how this contract shields the individual from certain encounters and knowledges. If a thing can’t be uttered in the open, its path to existence becomes more circuitous, is heaved beyond the realm of the senses, or is ontologically and discursively de-formed.

There’s much to be said about the sexual politics that initiate Sodom and Gomorrhah—so many of our dealings until now have been more obsessed with the impossible specter of desire than its satiation—and I feel certain (or else hopeful) that we’ll spend more time in the coming months on this aspect of the text. Proust himself began preparing critics for a narrative pivot in volume four from obscurity to transparency; as Benjamin Taylor writes, Proust’s correspondence in the leadup to publication was increasingly fixed on warning reviewers about the homosexual content of the book: “My characters don’t turn out well,” he informed Paul Souday, but “I must follow them where their serious defects or vices lead me.” We believe you, MP—no seriously, mama, kudos for saying that; for spilling. Part One of S&G feels more immediate from the jump, less baroque—its references are more liberal, and though not exactly contemporary with Proust’s milieu, are invoked in a way that feels more modern. There’s something about how Shakespeare arrives in this opening sequence that has the energy of a less esoteric text.

But I confess it’s felt strange and trying to sustain this project in the current moment. Not to say I believe Proust has nothing for the contemporary reader, but that—in a space where I enjoy total freedom as a writer—to write on the Search as if removed from a (the?) preeminent moral cataclysm of our time disorients and unmoors me; such a center cannot hold. I’ve written on a few occasions here about the ethical orientation of our attention; that is, how we make meaning in the space between what we look at and what we turn our faces from.4 Often this looking appears to us a choice, and we convince ourselves we can simply blot out what doesn’t serve, or doesn’t comfort, but everywhere now are brave and radical souls refusing to abide silence or allow anyone to feign blindness to or ignorance of Israel’s U.S.-backed genocide in Gaza. There is no peace to be pretended at; there is no looking away. In this crisis we’ve entered, instead, the age of disinformation, rationalization, and dismissal. In the latest issue of Bookforum, Hannah Zeavin responded to Aaron Bushnell’s act of self-immolation in solidarity with the Palestinian people. Almost immediately following his death, we “were asked to consider,” she writes, “whether [he] was the sanest American … his [protest] was taken up as an act about an individual, not an individual act performed with others in mind.”

Decontextualizing Bushnell’s sacrifice from the long political history of self-immolation—registering it, rather, as a fundamentally selfish act (the act of “the suicide,” imagined here as an unwell and irrational repudiation of bare life—for who, people wonder, wouldn’t want more life?)—reframes and delimits our mode of recognition in encountering protest. Such a view enables the cultural commentariat to persuade onlookers that the “crazier” thing happening now is Bushnell’s act of dissent—not the mass murder he protested from within the flames, his honoring of the literally countless numbered dead. As Zeavin writes, Bushnell knew before committing it that his action would be cast as anomalous, would be pathologized, and that our government and our institutions have already decided mass extermination is more customary and acceptable than revolutionary resistance. (During the week of this writing, I’d like also to point out that a person I feel lucky to call a friend has begun their hunger strike in solidarity.)

Meanwhile, on over 100 campuses across the country, student demonstrators risk suspension, expulsion, extra-institutional retaliation, and arrest to call for a ceasefire, and to demand the financial and academic divestment of their universities and colleges from Israel and its genocidal project. Establishment media, as Alex Shepard wrote this week for The New Republic, has chosen in their reporting on these actions instead to underscore internecine campus politics and the alleged “privilege” and “narcissism” of these students, while summoning vague specters of anti-Semitism within the protests (even while effacing well-documented video evidence of Zionist counter-protestors screaming “kill the Jews,” calling for a “second Nakba,” and telling young women in the encampments "go to Palestine! I hope they rape you"). All this of course works to obfuscate what is being protested to begin with—well over a million displaced people facing annihilation, tens of thousands dead, endless bodies discovered, unidentifiable, in mass graves with their hands zip-tied behind their backs, shot execution-style. The death toll has become largely immaterial—not because the horror has stopped, but because it’s become impossible to count that high without any ability to track who’s been killed.

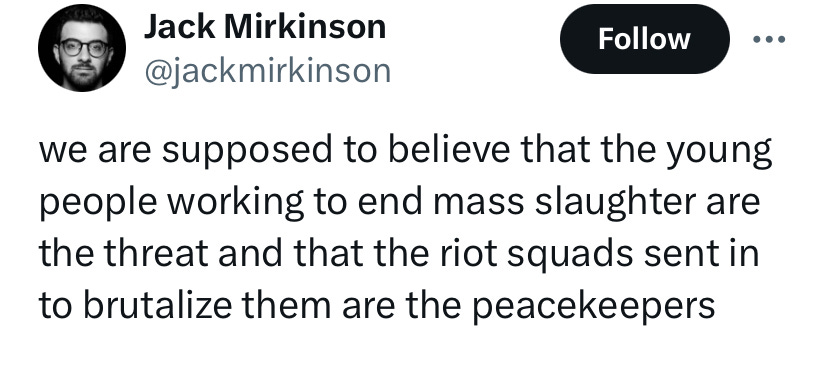

Such diversions are commonplace. Eric Adams and the NYPD paint the protests as filled and co-opted by “outside agitators”—what’s their evidence for this, you ask? They can’t say. News anchors refer to murdered six-year old girls as “Gazan women.” We are repeatedly instructed to imagine how “unsafe” Zionist students on these campuses feel in the face of signage asking for the end of a genocide, without any recognition of the actual, immediate, and totalizing threat Palestinian people face every day. Last night, twenty-four-ish hours after allowing counter-protestors to shoot fireworks into the encampments and beat up people inside it, LAPD officers shot students (“eating lentils”) with rubber bullets. Jewish anti-Zionists are called pathological and traitorous, or conspiratorially imagined to be paid dissidents at each turn. In response to campus protests, the House just passed a bill 320:91 which would functionally classify anti-Zionism as illegal anti-Semitism. In the comments section of nearly every post about the protestors you can find people lambasting their right to do it at all, rendering dissent as politically regressive or inert, calling this a “taste of trumps america”—as if the thing happening at present has nothing at all to do with the Biden administration, as if it is only a future echo sounding backwards. Protest witnessed through a convex mirror: if we can’t ignore the thing, we must remake its image.

I think often of the video from November of Palestinian children outside Al-Shifa hospital “inviting” the world to protect them: “we want to live as other children live.” Al-Shifa, of course, is rubble now—a mass grave. I pray for those children. I just don’t know how anyone can look away.

I’ll go on calling the narrator this, because it’s my fucking newsletter and I hate constantly typing out “the narrator”!!

Marcel’s spying here, of course, summons again the scene from Swann where he peers through the window to find the sadist Mlle Vinteuil and her female “friend” defiling an image of the late M. Vinteuil.

(Really there should be more trans readings of Proust, but I have other things in mind this month.)

Also want to point out, while I have the chance, how much I appreciated Raechel Anne Jolie’s recent writing on the new Alex Garland movie Civil War, an essay that I think is similarly wrestling with how to write about art now.

Great post and the importance of Proust’s work is always important in times of horrific activity. Dissent is important these days. It reminds me how bad trauma plays in the future. Thanks for your writing today.