I’ve been a neglectful mother. I know it and I won’t be shamed for it. That said, I’m negotiating ways of making a regular schedule here—i.e., returning to twice monthly letters—more sustainable. One approach is working in a more ranging fashion. This means that, while Proust will continue to be our primary beacon (and our reading timeline will continue apace), some dispatches will be mostly unrelated to his Novel—I’m inviting other kinds of writing in.1 My group chat offered solace by assuring me people read regards, marcel for me, and not for “fusty old Proust.”

So, from flooded Brooklyn, today’s dispatch—a sketch of the past, a shorter version of which appeared in Sloane Holzer’s recent surgery recovery fundraising zine, Augmentations.

In graduate school I knew the strangest man. Allan2 was nominally a scholar of Shakespeare, but his fixations, in the main, were on matters of bodily disturbance: plagues, the humors, the odder origins of Enlightenment thinking, scatological humor. He liked Shakespeare because Willy was a pervert. He liked James Joyce because Joyce was a pervert, too, a true savant of excrescences, particularly those oozing out of the orifices of his wife, Nora.3

Allan wasn’t much older than I was but walked, hunched into himself, as if incredibly aged, a pale and knobby sapling. He had a voice that sounded like a put-on: a cosmic, sonic joke that hummed somewhere between the melodious tones of Gilbert Gottfried and the innocuous catcalls of the oldest guy in the crew of grandads posted up outside the corner bodega. Allan put to rest any doubt about vocal fry’s capacities as a unisex phenomenon. I’m here to tell you that male fry is real, it’s frightening, and it had somehow reached its zenith in the throat of a 27 year old Jewish celibate from the Bay Area.

“You’ve got to read The Breast,” Allan would often holler at me—his sole volume was LOUD—“it’s by Philip Roth. A man wakes up to find he’s become a giant BREAST.” A likely premise. For years, or in any case for a single year, I put Allan off. No thanks, I’d tell him, I had some 155-lb talking, thinking, feeling breast earlier—I’m stuffed. I’d hated The Plot Against America, and The Human Stain interested me only inasmuch as Nicole Kidman starred in that dreary film adaptation. (Even she couldn’t save it.) We’d read American Pastoral for a seminar with the department’s most senior faculty member earlier that year, and I liked it as much as the next young, beautiful girl Roth would have preferred silence from, but must I be made to withstand 113 pages of him waxing philosophic on a loser professor’s literal occupation of female flesh?

In time, though, Allan wore me down. He was and probably remains a rather persistent type, and besides, I’m too patient with men. It’s the true curse I inherited from my mother. Allan and I rode the commuter rail together nearly every morning, and he never failed to remind me of this project he’d decided I was duty-bound to undertake. We finally agreed I’d read The Breast if Allan would read Anne Sexton’s Transformations, her collection of fairy tale revisions, and the book that had, in its roundabout way, led me to this graduate program. (I’d meant to study with an alleged Sexton scholar there—but that’s another story, one probably I shouldn’t air in public.)

I don’t recall what Allan thought of Sexton, or even if he read the book at all. He liked to get a rise out of me and the other woman in our cohort by exaggeratedly wagging his eyebrows and muttering things like, “she’s a real smart skirt” about the writers we loved and wrote on—Jean Rhys, Jamaica Kincaid, Virginia Woolf. We women would read all the boys’ beloveds because we had to, to be understood by our peers and superiors as competent in the canon, but the men were, of course, able to get away with skimming a single Toni Morrison novel, a couple Elizabeth Bishop poems, and, if they were daring, a lesser-known fiction by Joan Didion or Djuna Barnes.

Anyway, I don’t remember what I thought of The Breast either, although, as I write this, I’m preparing to re-read the novella, for a version of this story which will be smudged and ventriloquized for my next book. I find myself scanning John Gardner’s review of Roth’s Kafka-esque fable in the Times, seeking a clue—some madeleine moment—as to what I felt then, trying to dredge up from the stores of my memory whatever incendiary take I surely returned to Allan with. (For what it’s worth, Gardner calls it Roth’s most successful book to date at that time, but admits, as I suppose I must also have felt, that “the story doesn’t linger the way the best writing does.”)

Allan goaded and poked every woman he encountered, it’s true, but unlike many of the other men we staggered through the dull halls of the academy alongside, he was receptive to our parries, and thoughtful in his consideration of what we had to say. He bridled at sincerity but took us seriously, for he believed our voices were as necessary as his, though it seemed he’d never before thought to listen. Jean and I were ruthless. Allan seemed, in a way, to be something like our enormous son. We longed, or rather, needed, to raise this troublesome 27 year old boy into a good man, all his winking misogyny be damned. I don’t actually think Allan hated women. He was nervous around and intimidated by us, terrified, as men tend to be, that we’d laugh at him. (Of course we know where this fear can lead—to anger, to hate—come to think of it, Allan sounded a bit like Yoda, too.)

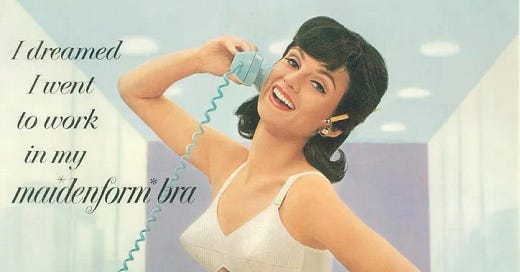

After I got my boobs done in January4—for they’re boobs now, or breasts, though not quite jugs, as terminology matters—I had, at last, my moment of involuntary memory, not because of Roth, but because of Sexton, whose poem “The Breast” surfaced, entire, from the caverns of my mind.5 It summoned for me those conversations with Allan and Jean, also my canonical frustratedness6, the whole mess of grad school and my misery then. I didn’t think much about my body in those years. I was totally dissociated, going a bit batty, really. It was augmentation that re-situated me in my past, brought forth another haunting.

“Later,” Sexton writes in that poem, “I measured my size against movie stars. / I didn’t measure up,” but for years I hadn’t thought to alter my breasts. I love my small tits, I’d insist to myself, they suit me, and anyway men worship them. Both of these things, of course, were true! I did look good before, and I look fab now! And the thing about fucking straight men that’s easy to forget is, though they have preferences, unless they’re James Joyce—relentlessly demanding an endless cacophany of bodily sounds and gases—mainly they’re pretty uncomplicated once the sex gets down to brass tacks.

My desires on the other hand always appeared to me illegible. I knew what I wanted to do for others, how I wanted to present my self for them, the ways I hoped to be readable to the world, but I rarely interrogated what it was that actually afforded me pleasure, because that’s trauma, baby! When it came time to decide if I wanted to get my tits done I remained ambivalent, and so I scheduled the consultation with my surgeon instead, thinking, I may as well while I have the insurance, and the answer would reveal itself to me eventually, in the course of the nine months between that phone call and my appointment. It did.

The thing is, I have a habit of denying myself things I want—or even considering what those wants could be—because I’m worried, always, if I expose myself to pleasure, to delight, it will be snatched from me at the moment of realization. Like my need had been conjured by a cruel god, simply to produce evidence of my incompleteness, the droning reality of my vulnerability to desire—that is to say, the condition of my humanity. The narrator of “The Breast” luxuriates in her body, her breasts, the flesh fact of herself, pointing out that “here is the eye, here is the jewel / here is the excitement the nipple learns … I burn the way money burns.” Money only burns in one way—decadently; its burning is total waste, a physical and ideological affront to capital.

Sexton was a deeply bodily poet—not only fixated on but delighted by our experiences of the grotesque and abject. I think she feared the dissolution of the mind, but the decay of the body, she knew, was inevitable, and attended, too, by the many countless pleasures of fleshliness. Her religious poems, for example, are obsessed with the body of Christ, Jesus’s corporeality, his physical capacities, his shit, his wounds, his sex7. I suppose I’ll relearn what it is I thought (or else didn’t) of Roth’s book shortly, but Sexton’s poem8, I remembered when it came again to me, disclosed to me a sort of revelatory glimpse of sensual self-presence, a reminder that this body is the only one I’ll ever have. I must be in it.

But now my kitchen is flooding, and it’s time to put this little body to work.

Next time: insomnia, Marie Darrieussecq’s new memoir Sleepless, volume 2, and a fall books preview. À bientôt!

I also felt reinvigorated by reading Charlotte Shane’s new substack, Meant For You, which I highly encourage you all to subscribe to. The first two letters are on romance novels and YA, and, as is true of all Charlotte’s writing, are not only intellectually incisive, but fucking hilarious and a true pleasure to read. Charlotte’s reminded me that this substack is a project I’ve taken on because I felt like doing it. It should be fun!

Needless to say this is a pseudonym.

Just read his letters to her—they’re obscene and strangely endearing. Nora is his little “farting fuckbird,” his “depraved blackguard,” his Norina, Noretta, Norella, Noruccia. I can’t say I’ve ever wanted a man to tell me he’s going to make my “cunt” a “wriggling” “mass of slime,” but I suppose other women out there should feel less alone.

I wrote about this process twice—most obviously in the dispatch linked above, but also, introductorily, here.

I should say here the piece is not from Transformations, to my mind Sexton’s most politically incisive book, but from Love Poems, her most vulnerable (or, according to JD McClatchy, her “weakest”).

In a literal sense—my frustrations with the canon we were being professionally assimilated into.

So, too, I think of Sharon Olds, and “The Pope’s Penis,” not to mention her wonderful book, Odes, with many of the poems there addressed to the parts of the body.

The poem itself remains radical, but the biographical contexts surrounding Sexton’s sexuality—her history as both survivor and perpetrator of sexual violence—perhaps shouldn’t go unspoken here. Diane Middlebrook’s controversial biography and Linda Gray Sexton’s memoir of her mother, Searching for Mercy Street, are the go-to texts. As I understand it, Heather Clark—the biographer behind the (to my mind) definitive biography of Plath, Red Comet—is at work on a new Sexton biography, which I am just over the moon about…

So good as always

Thanks for a great read. Your group chat is right.